Images of ‘Drug Wars’ today dominate popular perceptions of Latin America. The news is full of stories about cartel shoot-outs in Mexico, while television series like Narcos have made Pablo Escobar a figure familiar to millions. But what does the drug trade in Latin America really look like? How does it work? And why is it so violent?

Many commentators – and even policy-makers – blithely assume that today’s ‘Drug Wars’ are a modern phenomenon that dates back, at the earliest, to US President Reagan’s prohibitionist international crackdown on the drug trade, launched by in 1971. But the roots of the continent’s current conflicts stretch much further back in time.

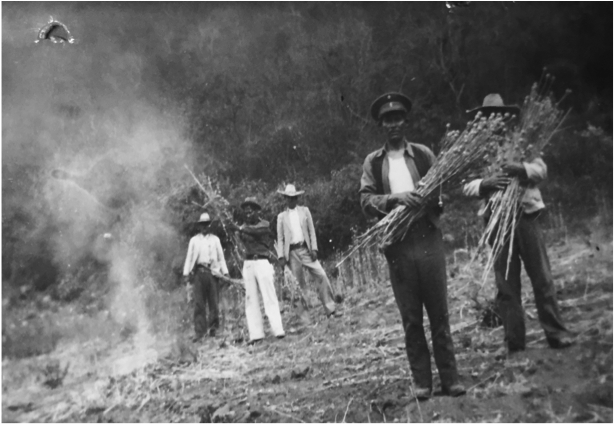

One of my post-doctoral projects looked at the deep history of drugs in Mexico. Above all, I focused on the ways in which the development of a profitable twentieth century trade in illicit commodities was inseparable from post-revolutionary state-building efforts, especially in the traditionally marginalised regions of the country that are at the centre of Mexico’s ongoing Drug War today. Naturally, this has had serious political, economic, and cultural consequences for these areas and the people who live in them.

Some of the key historical findings of this project have recently been published in a special, Mexico-focused edition of the Social History of Alcohol and Drugs – you can find it on their website, here [paywall], or get it free on my academia.edu page, right here.

I have also written about the severe economic crisis that the Mexican opium trade has been suffering since 2018, and possible ways of minimising its fallout on one of Mexico’s most vulnerable, marginalised and chronically-overlooked sectors: poppy-growing peasants. You can find more information in a free policy paper (published by the Wilson Centre), and or by reading this open-access article (in the Journal of Illicit Economies and Development), both of them co-written with Benjamin Smith and Romain Lecour Grandmaison.

I also teach a course at UCL called ‘Cops, Cartels and Cash Crops,’ which examines the development of drug production and trafficking in the Americas more broadly. It assesses the role of the region’s governments – including the US – in the development of the contemporary drug trade; looks at its impact on local societies, political systems, economies and cultures; and pays special attention to both academic and popular/media portrayals and understandings of the drug war, and the effects of drug use, production and drug-related violence on marginalised groups like indigenous peasants, disenfranchised youth, and women.